MYSTERY & POWER ON EVERY PAGE

SO, how is your mystery screenwriting going?

SO, how is your mystery screenwriting going?

What, you say? You’re not writing a mystery?

Oh, but you must be! You really must.

The reason I insist is because, in the scores of spec screenplays I read and analyze each year, there’s hardly ever enough “mystery” to pull in readers and hold them. And that’s especially common in the scripts by writers seeking to “uplift” (these make up about half of my clients)!

Now, in my work as a script doctor, I typically don’t start with a focus on the mysteries in a story.

What’s usually needed first is lucidity on the “big-picture” items, such as plotting out your characters’ functions, goals and problem-solving frameworks; your specific thematics and their progressions; your four essential throughlines; and so on through “The 12 (Or So) Essential Questions.”

Like it or not, if you want to construct a truly solid, properly balanced story that ranks among the best, you really need to first answer these logical, ground-rock questions, then get into trying to make the story mysterious. You must know “what there is to reveal” before you begin deciding how, when and where to reveal it to the investigating characters (and the audience).

Writing everything “mysteriously”

But then, once these big questions are answered, you’d better quickly make sure you’re writing mysteriously as you present these cohesive-and-integrated choices on your successive pages.

And please don’t think I’m just talking here of mysteries like The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Chinatown, or L.A. Confidential (just to name a few in this highly popular genre).

I am talking about the mysteries in your comedy. In your inspirational romance. In your family drama. In your coming-of-age story. In your whatever.

In your heart, you know this is essential: Every compelling story’s got to have a good lot of mystery to it, else why should we pay attention? It’s got to have some mental provocation, some hidden promise, some tantalizing prospect that intrigues, makes us curious, and compels us to read on through each heated, secret-laced page (even if they’re hilarious pages too!).

You are writing mysteries, even if there’s not one tough private eye, hard-bitten journalist, or dutiful detective anywhere in your script’s neighborhood (though you’ll never be able to do without some characters who exhibit “inquiring minds”).

You still need mysteries on every page — little incongruities, little niggling anomalies, little hints that there’s much more here than is currently clear… but the haze seems to be dispersing. And the revealing of new “mysteries” and deeper “mysteries” should keep on coming, page by page.

When power peeks out

So how do you do that? Amid the confusion that writing can sometimes be, the way here is simple: All our feelings of mystery and intrigue rise, in one way or another, “when power peeks out” — that is, when we gets hints that (to rework Flip Wilson) “What you see is only the tip of what you might get.”

For proof, look at almost any page of a successful screenplay; probably without trying hard, you’ll see mystery engaging you as various powers “peek out.”

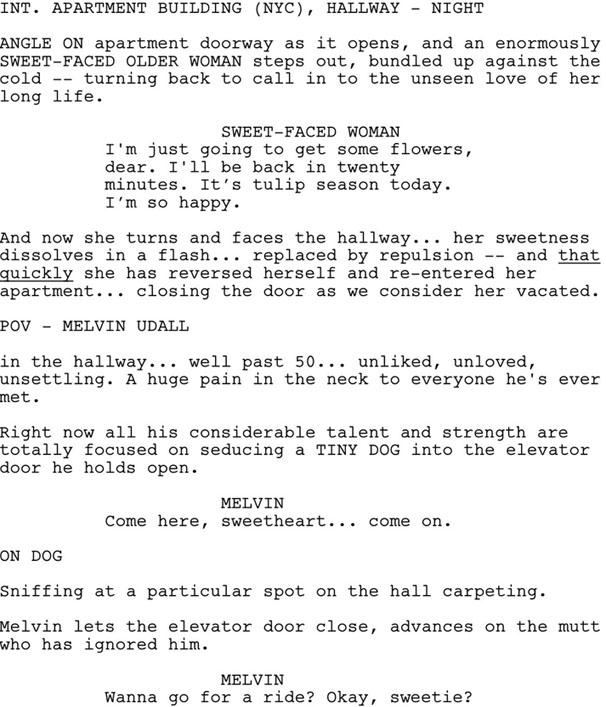

So, how might you create compelling mystery when you’re dealing with, say, an obsessive-compulsive hermit who avoids people as much as possible, and if at all possible would avoid hurting even a flea? Let’s look at how Mark Andrus and James L. Brooks made mystery, on a comic page 1 you may well recall:

Do you see and feel the mystery here? Even knowing that this is from the huge comedy hit As Good As It Gets, and how the story all works out, we can still sense this scene arousing our curiosity:

What has the Sweet-Faced Woman seen that so alters her temperament and intentions? Oh, an “unliked… unsettling” man (and note how little is actually said here about Melvin’s physical appearance, because that’s not where his power lies).

Then we’re asking ourselves, what has this man done to cause such a reversal in the woman’s mood?

Next, what are this “huge pain in the neck’s” aims in trying to “seduce” a tiny dog into the elevator?

For that matter, why would a man of such “considerable talent and strength” be “totally focused” on using such a roundabout approach to get a tiny dog to follow him?

And assuming the Sweet-Faced Woman is wise in her assessment of Melvin, then what is this fellow ultimately capable of?

Recognizing “powers”

What “powers” do you see “peeking out” here? Well, I start with seeing the Sweet-Faced Woman’s powers of love and warmth and hope and delight — which are quickly counterpointed by Melvin’s apparent powers of unlikeability, hostility, repulsiveness, meanness, etc.

And that meanness, not even aware of the Sweet-Faced Woman’s reaction, has its concentration focused on the little dog — which possesses, among others, the powers of cuteness, innocence, guilelessness, (eventually) adoring acceptance, etc. Seen this way, the powers at work in the scene are endlessly absorbing! And they continue developing and emerging right up to this Oscar-nominated screenplay’s warmly funny conclusion.

Similarly, you should never run out of powers to play with in any of your scenes. That’s because 1) every character and situation should possess more power than it initially evidences; 2) no exhibited power should ever go fully unopposed in any scene (except perhaps in your denouement); and 3) no power should ever reveal all of itself in any scene except at the climax. It’s important to note that power itself is not necessarily mysterious. If a power is too obvious in its manifestation, we’ll likely read it as empty pretension or faulty foreshadowing.

But power “peeking” — ah, that’s what makes it intriguing. Glimpses of the glow, the edge, the aura, the tip of some as-yet-only-partially-revealed power — that shall keep us reading to find out exactly what makes up the rest of that peeking-thing’s strength. And once all its muscle is revealed, your story had better be racing to its conclusion.

While you should not introduce new characters too late in the story, your principal characters can (within reason) certainly display new powers up to the last seconds of the climax (as in that last-gasp grasp to reach the untapped, deep-within-oneself virtue — or villainy — that surprises even the character exhibiting it).

And this ultimate exhibition should quickly lead to the final clear victory for whomever you want to win the day. For instance, all Melvin’s meanness is overcome, ultimately, by the love of, and his love for, Carol the waitress and her son.

The history of mystery

Mystery in writing is as old as humankind, and should become the forte of any committed fiction writer today. Both the Old and New Testaments frequently invoke mystery (such as Proverbs 30:18–19’s very-instructive discussion of the mysteries of nature and man), as do the ancient Greeks, the Romans, and Shakespeare.

Yes, so much more could be said about the “mysterious ways” we writers can evoke intrigue and page-turning in our readers — I can only show you “the tip” for now…

And I recommend you learn all you can from books on writing actual mysteries, such as How To Write Mysteries, by Shannon Ocork, and Writing the Modern Mystery, by Barbara Norville (both from Writer’s Digest Books and available in public libraries).

For specific help on pumping more mystery — and power — into the specific story you want to sell to Hollywood, contact us right here at Keys2ScriptSuccess.com!

Or, you can break into the old warehouse on the darkened corner of Spilsh Street and Crick Ave., where deep in the back there’s an — AACCKK!!!…